Asia Pacific Triennials and music festivals

A memoir spanning three decades from 1993: nine APTs and too many music festivals. Growing up with a backdrop of Asia-Pacific art and a soundtrack of live music.

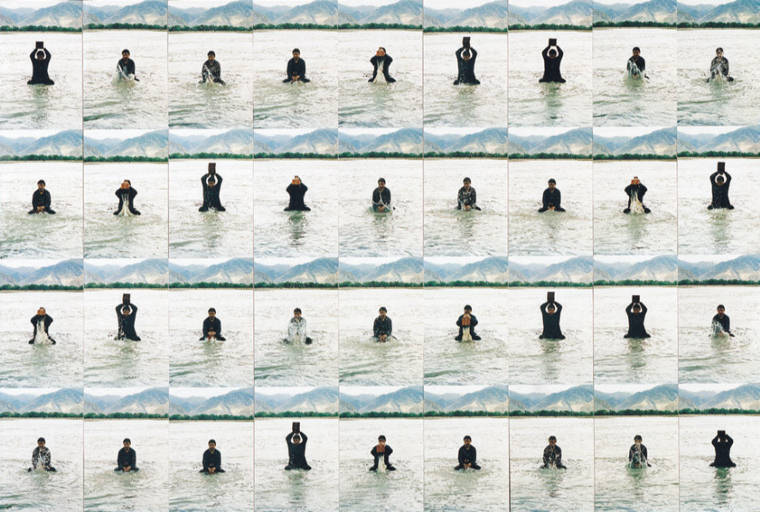

IMAGE: Caroline Gardam

The Asia Pacific Triennial: music festival, but Art.

Queensland Art Gallery/Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA)’s Asia Pacific Triennial (APT), like a good music festival, delivers unplanned discovery. There for the headliner, you uncover treasure around unexpected corners. These bonuses deliver the joy of each festival experience. Both (APT and music festival) are curated for spectacle. Both encourage altered states.

I’ve never missed an APT, and only childbirth, surgery, or overseas travel kept me from Splendour in the Grass. I attended the first APT the same era as my first Livid festival. Both were all about experiencing the festival itself, not seeing individual artists: a gestalt of aesthetics or atmosphere, if you like. Both exceeded expectations, electrifying a lifelong bond.

The first APT certainly exceeded expectations. We had none.

Brisbane, 1993

Brissos had no idea what to expect, but seemed to enjoy the treats on offer at this novel contemporary art exhibition. Of course, it was the early 90s: we were up for it. As it turned out, we were up for more than we’d even considered.

For me, like many Queenslanders, the first Asia Pacific Triennial – APT – was my initial conscious experience of Asian contemporary art, certainly the first I remember noting. And such abundance, right under our sunburned noses! Sure, ‘twas far from perfect, attracting some criticism. Funny how even criticism varies with the times. Twenty-eight years of hindsight hones an awareness of the epoch’s particular oddities and curatorial prejudice, as well as an understanding of how these infelicities tended to flatten out across APT iterations. How quaint now, for example, the idea of grouping artworks geographically! But overall, what an array of cleverness, ferocity, beauty, and depth – peaking with Dadang Chrisanto’s performance “For those who have been killed” in a forest of bamboo poles – a performance that began with the artist covering himself in clay (puzzling accidental onlookers in quotidian Queen Street Mall) before advancing over Maiwar/Brisbane River to resolve as shamanic dance amongst an installation of bamboo and metal poles in the Queensland Art Gallery.

Christanto’s political activism mirrored this then-twenty-something’s recently graduated sentiments. Social justice and environmentalism dominated the spare headspace not reserved for live music. I lived with bands. I volunteered at Greenpeace’s new Brisbane office. Kamol Phaosavasdi’s “River of the King (water pollution project one)” politicised QAG’s waters. In an exhibition oft described as ambitious for what was then considered a “lesser” Australian gallery, new voices rose to be heard. Or smelt. Pungently punchy, Bul Lee’s “Fish” – a freezer full of embroidered, sequinned, ah, fish, delivered a frisson. And, later in the summer, a certain whiffiness.

Despite APT’s role as an expectant non-colonial introduction to the first group exhibition of its kind – ever – of artists in the region, an opaque colonisers’ curatorial framework is evident, staining the view when observing backwards from three decades hence. Despite this near parochial framing, an enduring memory was to view indigenous Australian artists within the exhibition’s wider regional context: artists such as Kathleen Petyarre and Judy Watson, shining in place in an international spotlight.

1993 was a winning year in the history of fringe Brisbane music festivals. Like the first APT, many of these independent little festivals backed un- or to-be- knowns, and you’d go along to listen, dance, and discover. These were the grunge- (or patchouli- ) tinged days of Brisbane music – the era of Clag, Blowhard, Screamfeeder, and of Powderfinger’s luscious locks. Of Tiddas, the Toothfaeires, and Custard.

October 1993 began with the Livid festival and wrapped up at 4ZZZ’s Octobanana Market Day, a mini-festival with all local acts – almost all unknown to me; the only name I remember now is Acid World, patently titled for the times. Somewhere in between hung 1993’s West End Festival, which filled Boundary Street with party and made us realise that some backpackers are easy to shock. Livid fused music with a little art, and like the APTs, rewarded the brave with unexpected treats: Beasts of Bourbon, Siouxie and the Banshees, Ed Kuepper, and an all-nude offering from New Zealand’s Head like a Hole.

And nobody took pictures at gigs back then.

A month later, I slammed Powderfinger’s long-haired Transfusion EP CD into a Sony Discman and boarded a Qantas rite-of-middle-class-passage to Heathrow, taking my region with me in punchy tunes and aesthetic memories. APT, like Livid, had assembled a barely subconscious frame of reference for consequent travels; later, I felt tethered to the region despite roaming European institutions, devouring exhibitions and laser-lit dancefloors, and bloating on stodgy Western artistic offerings.

1996, back in Brisbane: older, grimmer

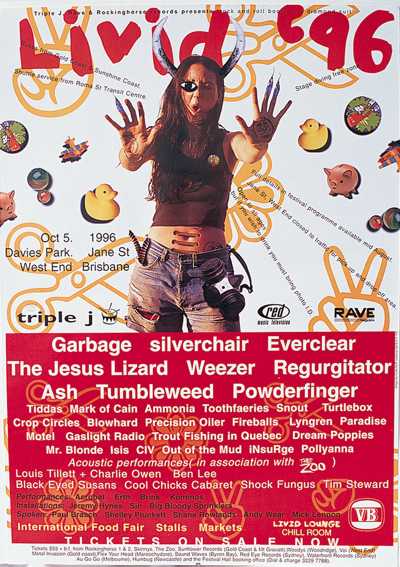

The Livid festival of 1996 occurred a fortnight after the second APT opened. Grunge was still king, but crown pretenders lurked. A couple of months later, the Big Day Out’s headline act for 1997, Porno for Pyros, appositely embodied the mood.

At APT2, Cai Guo Chiang’s much-anticipated Brisbane River explosion project “Dragon or Rainbow Serpent: A Myth Glorified or Feared — Project for Extraterrestrials No. 26.” was cancelled following an accidental explosion at the fireworks company the day before the scheduled event.

In hindsight, this feels like a particularly “1996” brand of happening.

Like viewing Zhang Xiaogang’s “Bloodline: The big family” for the first time. These faces, flat and detached, gazing from a changing China to a shrinking world. I spent days gazing back at them grasping for some kind of answer in the fug of mid 90s’ existential angst. Whether a personal crisis or something more aligned to Generation X’s moody sensitivities, APT2 responded in kind.

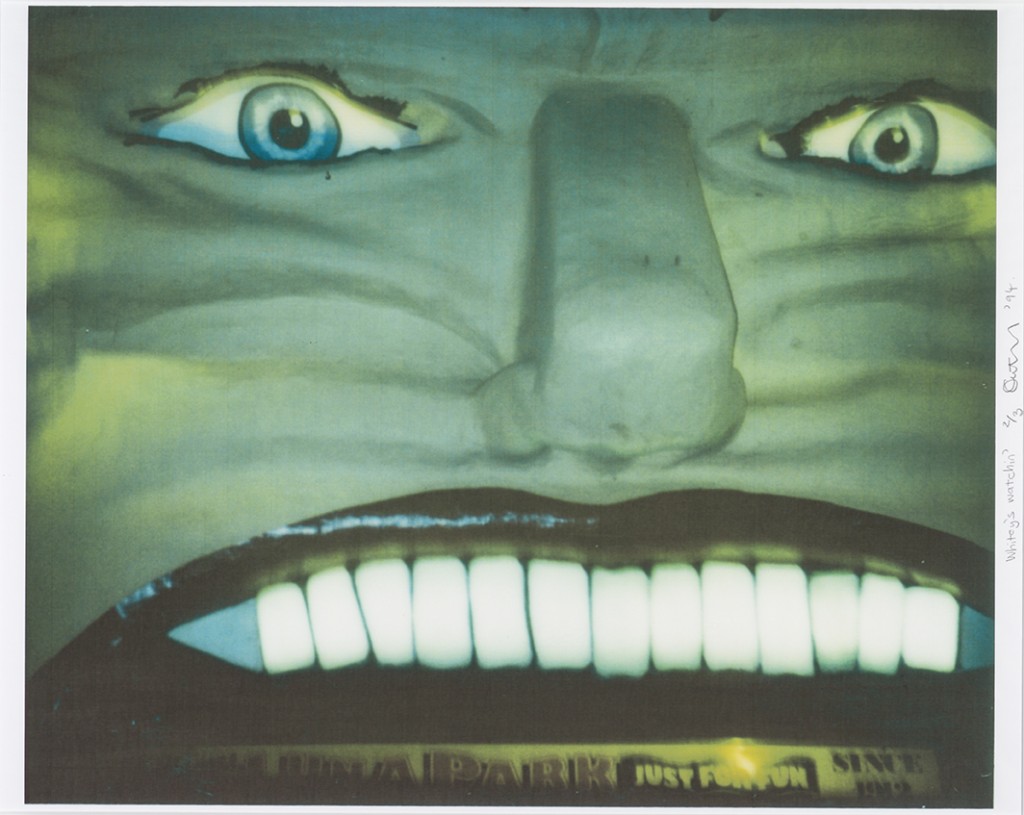

The knives were out for consumerism. Fiona Hall’s “Give a dog a bone”, and the Campfire group “All Stock Must Go” speared consumption and the cheap commodification of Aboriginal art. I stared back at Destiny Deacon’s “Whitey’s Watching”. She won.

The contemplative complement was Denise Tiavouane’s “Crying Taro”. Taro, alive and growing, crying with the recorded sounds of women from New Caledonia’s northern province. I wept: 1996, indeed.

But like a chink in a festival’s black-clad lineup, allowing a glimpse to a techno-shimmering future, APT2 let space for clever kitsch, like Takashi Murakami’s iconic hero image “And then, and then and then and then and then”, and the work of Jeong Hwa Choi and Yun Suk-Nam. There’s a crack, that’s how the light gets in. Just like 1997’s Big Day Out on the Gold Coast, where the Prodigy was offered up alongside Soundgarden, but also Shonen Knife, Tiddas, Bexta, and the Superjesus, 1996 was complicated. Discernable fun glinted from the darkness. I walked out Livid’s gates with my purple mini and striped furry little T-shirt covered in dust, and ended up driving through the streets of Brisbane with a drag queen’s feather boa fluttering to the street behind us, as we arose waist-high through a stranger’s Mercedes sunroof. From the dust of Silverchair to the sequinned-strewn dancefloor of Sportsmans Hotel.

For APT3, we partied like it was 1999.

Riding high, APT3 – like 1999 – whizzed past, a ferocious speedy clash of past and future, precious and superficial, brash but thin-skinned. At the time, it all appeared loud and fabulous. Looking back, you can imagine who’s bluffing.

I published and edited a street magazine, and my business partner and I lived off the spoils of independent publishing: hors d’oeuvres and beauty product samples. We were skint and skinny, but shiny, writing arrogant 300-word pages, and the third APT was our match. APT3 launched alongside our 8th edition, a few weeks before Livid #13. The soundtrack: less guitars, less grunge, more electronica, bigger basslines.

With the theme “beyond the future”, this APT3 was a biggie: it added Niue, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Wallis & Futuna, it now involved 50 curators, and it introduced a brave new kids APT (but about this, I was yet to care). APT3 felt like we’d jumped a few rungs up the ladder. And, in a state where far-right ultranationalism visibly seethed, the openness of Queensland (and visitor) audiences to experience vivid multiculturalism warmed the heart. Fuck off, One Nation, we cried.

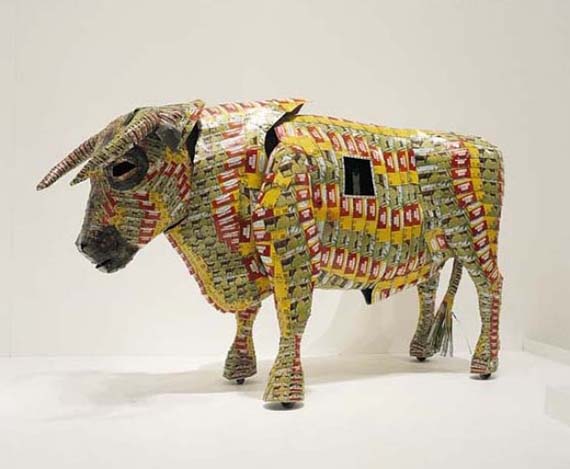

The moments were big, the performances huge and designed to please. Cai Guo Chiang’s earlier fireworks had fizzled, but he built a bridge for 1999 that charmed all. The Tulanan Mahu Niue collective presented “Shrine to Abundance” in a shipping container. Katsushige Nakahashi’s “Zero” created a massive fighter plane from photographs and gaffer tape. “Clashing of the bulls” described a cute “one night stand” between Michel Tuffery and Patrice Kaikilekofe.

The gallery shone like a glossy blockbuster, yet, in some corners, intense ideas smouldered. Experiencing Gordon Bennett’s “Notes to Basquiat” for the first time is an exact embodiment of art’s “aesthetic arrest”. I returned to this work three times during APT3. In a different space, I found Vu Than’s “Promenand dans la nuit” dark, primitive, proud, and endearing.

APT3’s enduring gift: experiencing Mella Jaarsma’s work “Hi Inlander (hello native)”. Hijabs of chicken, frog, and kangaroo skin literally placed one within another’s skin. In-skin performers cooked a variety of meats for the public. This work, in that political climate? A festival moment.

The Livid Festival in 1999 had, similarly, split its breeches, and moved to the RNA showgrounds to manage a growing popularity. Livid’s source base of acts, although shrunken in variety, nevertheless offered a broader scope than the competing Gold Coast juggernaut. In January, a massive Big Day Out line up included blockbusters Red Hot Chili Peppers, Nine Inch Nails, Chemical Brothers, and Foo Fighters, alongside Basement Jaxx, Yothu Yindi, Resin Dogs, Spiderbait, and, *sigh* Blink 182. Beyond blokey, this was machismo to the max. The late 90s could be like that. Enter the millennium, men.

A stiller river, running deeper

Whether it was a response to critics of APT3’s hyperactive breadth, or a seismic shrink back from millennial craze, but APT4 (2002/2003) saw fewer artists create more works in a tidier display of substance.

In 2002, invited to the APT4 media call, this year I would selfishly chose to write for no-one – just quietly engage, often alone, with the exhibition for a couple of discreet hours.

This was how I experienced Kusama’s “Soul under the moon” for the first time. Alone. Unprepared. Open. Ready.

At the time, Kusama said of the work, “I want visitors to look at the dots, and feel a freeing up of the soul. Then, taking that feeling of freedom, look into the work and have their goals and fears revealed. That’s my aim.”

I couldn’t write 2002 any better.

It’s loved to cliché these days, but “Soul under the moon” was revelatory on a virgin visit. To hear the doors slide back, to walk along the gangplank into the still space where Kusama’s fluorescent dot universe expanded in reflection… to be serene, meditative, and still. I confess: I can’t bear to share that space with anyone when it’s exhibited now.

Kusama was one of art’s “elders” presented in a considered exhibition, alongside Nam June Paik and Lee U-fan. From a galaxy of over 70 artists in 1999, APT4 showed 16. Kusama also debuted the dotty Obliteration Room, alongside Lee U-Fan’s zen restraint, Michael Ming Hong Lin’s walls of delightful floral excess, the glorious Pasfika Divas, and Nam June Paik’s whimsy. That year, I shared my soul with Michael Riley and Song Dong, as well as Yayoi Kusama.

Meditative exploration in Song Dong’s “Stamping the Water” generated a work of purity and intelligence. Michael Riley’s Cloud series, an application of new digital technologies, combined confronting elements of his history within exquisite beauty. This was a heart-expanding APT.

The 2002 Livid festival had grown larger, but fun was to be found in the fringes. Like this year’s APT, it was curated to provide a deeper experience for more punters. I joined a core of fans for george’s cranking set scheduled at the same time as Oasis. Although george were Brisbane locals, it was the festival of international distinction around them that framed and lifted the performance – a similar framing that local artists experience as part of APTs. Later, as the ridiculously talented Noonan siblings celebrated alongside their George bandmates, one of the Gallagher brothers sat in a grimy Zoo corner at Livid’s afterparty, stormy gaze under those living brows keeping all comers at bay. Just as not everyone is into Oasis, Oasis wasn’t into everyone, either.

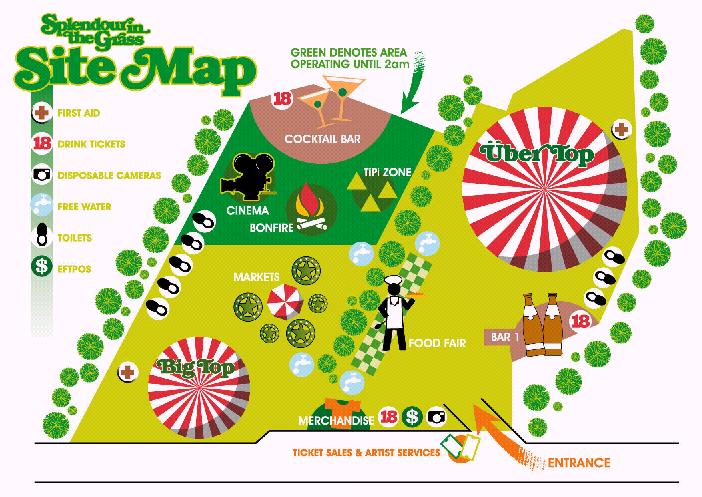

Another festival aspirant, Splendour in the Grass, launched in Byron Bay the previous year, and the second Splendour grew into a two-day journey featuring overseas and local acts including Supergrass, Gomez, and Machine Gun Fellatio. The first two years of Splendour were also beautifully curated to encourage maximum heart expanse. We walked from the festival site into Byron town at the end of each night, a flowing punter creek of post-festival silly conversations.

APT5: growth

By 2006, I was living on the Sunshine Coast with a two year old and a seven-month-old, both of whom I enthusiastically left at home with their father to attend the media preview of APT5 in the new Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA).

It had been many months since I’d been to a gallery, a fact that should be bloody obvious when reading the previous sentence. I was breastfeeding my youngest; it was crucial to pack a pump in my handbag to make our long day apart happen healthily. I forgot it.

I’d mastered the “pump-and-dump” at 2006’s Splendour in the Grass, cloistered in the calm sanctuary of a St John’s tent (manual manoeuvres hastening as the opening bars of Sonic Youth’s set knelled across the field). Splendour had escalated to a serious international event, dominated in 2006 by American acts, with a studied approach to assembling acts. Scissor Sisters to Yeah Yeah Yeahs to Augie March to Paul Mac. Not so much a south pacific schooner’s voyage of discovery as cruise ship buffet.

APT5 (2006/07), the first exhibition at the new GOMA building, could also afford its headliners. Two buildings, twice as much fun: this APT was massive. It allowed the space for Ai Wei Wei’s shimmering “Boomerang” over QAG’s watermall, dazzling in its wit and its crystal, with Bharti Kher’s “The skin speaks a language not its own” on the floor above. Space to show Dinh Q Lê’s installations. Space for Anish Kapoor.

Space also for the bark paintings of Diambawa Marawili, Sangeeta Sandrasegar’s immaculate paper cuts, Qin Ga’s “The miniature long march 2002-05” (tattooed on his back), and the puzzling Eko Nugroho… we gobbled. This APT had grown up, another set of rungs up the ladder.

Like a festival, now there was also space to walk away, to not view, and to not feel ripped off in the process. The new gallery offered space to chose.

In the new GOMA cinema, a Jackie Chan retrospective revealed a nose for populism, or curatorial irony? Whatever; we love Jackie Chan.

After an engorged day at the launch, I didn’t stay on to experience Cornelius, or Stephen Page’s “Kin”, to my regret. I returned the following year to splurge more time with the Pacific textiles project, among others. That’s something you can’t do at a festival.

Healing

Early 2009 had me working through physical challenges that rendered me near mute. Art, particularly within a larger gallery’s healing stillness, acted occasionally as therapy. I spent a chunk of solo time in GOMA during 2009. I’m not sure I saw much live music. I don’t think I went to Splendour that year; I can’t remember.

In the three years following GOMA’s unveiling, we’d decided to return to Brisbane and this new gallery was one anchor of domestic choice. Moving back to Brisbane with young children, we met some new parent friends who, for a little while, never knew me with a voice. That was weirder for me than them, I suppose.

It made for a long slog, the beginning of 2009 through to December, from being a bundle of physical tics in February, through September’s somewhat coordinated flash mob dancer, to near-regular physical condition in time for APT6 at year’s end. After months of physical and mental trial, settling somewhere safe. This APT was one for me, and one to share with the kids.

But first, alone. If I could have moved inside Tracey Moffatt’s “Plantation” series and lived there, I would. I loved Moffatt’s “Other” so much, I stayed and immediately watched it through twice more. Then indulged solo time with Sopheap Pich and the ni-Vanuatu Mataso printmakers.

When I returned with children, like 1000 others, I perched them in front of Shirana Shahbazi’s “Still life: Coconut and other things” and took a photo. I showed them Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian’s shimmering “Lightning for Neda”, Subodh Gupta’s “Line of Control” (a mushroom cloud of kitchen utensils), and of course Kohei Nawa’s super popular glass-ball taxidermy triumph “PixCell-Elk 2”. (I tried to get them interested in work by artists from the DPRK, but no luck.) APT6 appeared to be the prettiest, the most accessible yet. Safe.

The twenty year mark homecoming, and adulthood

In November 2012, the Harvest festival sprawled through Brisbane’s city gardens. We’d been excited for months. Santigold AND Silversun Pickups? Please! Silversun Pickups cranked our afternoon. But the subtropics had a stormy surprise waiting, and wild weather closed the festival temporarily. The sea of rain ponchos in fading light created a surreal unplanned installation. We retreated, and chose the comfort of home over returning to a muddy amphitheatre when it reopened an hour later.

Marking 20 years of APT, APT7 (2012/2013) showed more indigenous Australian artists than any prior APT. Michael Cook’s Civilised series was another kind of homecoming, though not necessarily comfortable, stunning in its motifs. Greg Semu anatomized colonisation in “Auto portrait with 12 disciples (from the Last Cannibal Supper… cause tomorrow we become Christians series)”, work that slapped you with resonance. Both Cook and Semu’s work encouraged me to consider, in depth, our history of occupation and empire. Seeds of decolonisation were nurtured.

Daniel Boyd’s installation “A Darker Shade of Dark”, using dot painting techniques as a lens, was partnered with a cool kids APT activity. We enjoyed both kids and “real” Boyd. I’m grateful for GOMA’s adult-child scope, but I fear my offspring may be humouring me when we visit APT kids. That said, we did have a lot of fun with Kazakhstan holiday photos in 2012 (Erbossyn Meldibekov “Family Album: From Queensland To Kazakhstan”).

The work I returned to more than once? Kwomba Arts sculptures and paintings and Abelam’s Brikiti Cultural Group’s Korumbo (Spirit house) structures from the East Sepik Province of Papua New Guinea.

The work I could look at forever? Takahiro Iwasaki’s elegant, delicate, detailed “Reflection Model (Perfect Bliss)” which combined exquisite technique with deep thought.

Movement

My personal experience in APT8 (2015/2016) was bookended by installations on the ground and third floor galleries of GOMA. Upstairs, Yumi Danis (We Dance) choreographed by Marcel Meltherorong (also known as Mars Melto) inside “They look at you” by Kanak artist Nicolas Molé, on the opening weekend of APT8, presented an uplifting triumph. On the first floor, Rosanna Raymond’s SaVAge K’lub turned on cultural stereotypes of “otherness”.

The first floor was dominated by Asim Waqif’s installation “All we leave behind are the memories”. Massive and clever, but cold. APT8’s warmth was in bodies. The SaVAge K’lub’s bodies, the Yumi Danis bodies, and Christian Thompson’s body as described in his Polari series.

Bigsound, in 2015, was a music industry conference that at night adopted the mood of a festival, lurking around the streets of Fortitude Valley. Unknown and unsigned bands played short sets in bars around the valley. It was awesome. It still is. You make discoveries.

I discovered Danie Mellor at APT8. His “Deep” was my art crush that year. I would leave meetings in Brisbane city, walk across the bridge, and detour on the way home just to spend some time with him. I also fell for Segar Passi and Gunybi Ganambarr (particularly “Nganmara”), but Mellor, to this day, has my devotion.

I have a photo from Splendour 2015. My friend Roland took it. It’s Jai and Kate and me and Sandy in his pink beanie and Fancypants and Jacinta leaning out the backstage bus window at the Tackleshack, late in the evening one night – Florence had long finished. I think it’s the same night Kate and I scored a lift with JC and a security guard in a golf cart across the site back to our camp to drink smuggled Champagne. It was a muddy festival but we had gumboots, VIP passes, and a borrowed camper trailer. I think this was the year where I realised (1) we were definitely too old to be members of the dominant festival generation, and (2) this is good.

Circularity

We made it down to Byron in time to enjoy juicy chunks (MGMT, Gang of Youths, Ball Park Music) of 2018’s Splendour in the Grass. So massive now. Many of our old playmates brought (or were brought by?) teenage children. We’d escaped our own brood and chilled languid in a dune-tucked airbnb (a falé with op-shop furniture and inside-out architecture: shower, kitchen, and toilet all bolt-on externals), summoning the energy to deal with dust and people. Managed some old-school moshpit mayhem with our regulars, froze when not squeezed in the front row around the Gold Bar’s bonfire bonhomie, and skived the main event, Kendrick Lamar. It was the first Splendour I’d ever left before the end.

Later that year, as APT9 launch weekend loomed, I was dizzy with anticipation.

Producing videos of interviews with artists and arts organisations for arts media entity, POPSART, meant I occasionally found myself filming inside the cool sanctuary of QAGOMA. Not just for that aircon am I grateful; I am sharply conscious of the fortunate position of access that media can enjoy.

The morning before APT9’s doors opened to the public in 2018, GOMA’s ground floor hosted unique, international majesty. Weavers from Bougainville and the Solomon Islands, here for the Women’s Wealth project, sat in Mother Hubbard dresses and floral wreaths in front of tidy Japanese artists, Hawaiian curators, and media of every shade arranged politely around Bounpaul Phothyzan’s “Lie of the Land” (literal) bombshells. POPSART interviews included sound installation artist Yuko Mohri; Lisa Reihana in front of her work, “In pursuit of Venus”; and Taloi Havini, whose film “Habitat” – using archival and current footage involving Bougainville and its copper-cursed history – carried the interview into an unprecedented, contemplative zone where dialogue subsided, leaving us dumbstruck.

Work duties complete, I snuck away to explore again, alone. Johnathan Jones, in conjunction with Uncle Stan Grant Sr, brought the Wiradjuri concept of giran to Kurilpa. Shilpa Gupta, whose fabulous “24:00:01” had been hanging at the top of the first floor GOMA escalator for a few weeks in APT-anticipation, gave voice to 100 poets who have been jailed over the centuries for their writing or politics in “For, in your tongue, I cannot fit.” Revisiting both a number of times over the following months, I occasionally experienced these works in contemplative solitude. Shilpa Gupta was this writer’s artistic find in APT9, a mind-massaging joy. This work lost none of its potency when viewed among a viewer-throng during the Venice Biennale the following year.

Festival-like, APT9 delivered unexpected discoveries around corners. Aditya Novali’s “The Wall: Asian (unreal) estate” demanded return scrutiny, while Waqas Khan’s fastidious pen-technique (he uses a 0.1 Radiograph, over and over) presented an engrossing highlight. Mao Ishikawa photographed the freewheeling mid-1970s women of Okinawa, the engaging images revealed in prints discovered by the artist’s daughter. Kapulani Landgraf’s collages were like old companions I’d forgotten I had.

The next day I returned with my family for the kids’ APT program, particularly Jeff Smith Mauri’s “Tungaru: The Kiribati Project” (we became part of a coral reef) and Jakkai Siributr’s “The Legend of the Rainbow Stag” (we became part of the stag’s story).

Like a music festival where you travel from one stage to others, then back, I called in sometimes over the following months, grateful for the city in which I live. Unlike a music festival, which often loses its charm when it grows too large, an APT can hold onto a larger local audience through summer’s repeat-visit benefit.

APT9 claimed one of the largest representations of First Nation artists to date, and the majority of artists, for the first time, were women. That particular future was indeed female. APT9 remained a journey, but a journey taken over a circular path.

Covid-19 killed live music.

Delayed until it could be delayed no longer, delayed into oblivion, Splendour in the Grass’s 20th anniversary festival, in 2020, was cancelled due to Covid-19. Bolting the door on all yesterday’s festivals, that year rudely punctuated life: an underline? Period? My festival days are gone, maybe yours too.

As I write, the future of festivals is still unknown. And APT?

APT10 is scheduled to begin on 3 December 2021 at QAGOMA. Let’s meet there.

Selected references

Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art. (1993). Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art: [catalog]. South Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery.

Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art. (1996). The second Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art: [catalog] : Brisbane, Australia, 1996. South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia: Queensland Art Gallery.

Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art. Brisbane, Q. (1999). Beyond the future: the third Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art. South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia: Queensland Art Gallery.

Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art Brisbane, Q. (2006). The 5th Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art. South Brisbane, Qld.: Queensland Art Gallery.

Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art Brisbane, Q. (2009). The 6th Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art. South Brisbane, Qld.: Queensland Art Gallery.

Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art. & Gallery of Modern Art (Brisbane, Qld.). (2012). The 7th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT7). South Brisbane, Qld : Queensland Art Gallery

Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art & Gallery of Modern Art (Brisbane, Qld.). (2015). APT8 : the 8th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art. Queensland Art Gallery, Gallery of Modern Art, South Brisbane, Qld

Green, Charles. “Beyond the Future: The Third Asia-Pacific Triennial.” Art Journal, vol. 58, no. 4, 1999, pp. 81–87. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/777914.

Seear, L., Queensland Art Gallery. (2002). APT 2002: Asia-Pacific triennial of contemporary art. South Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery.

http://www.visualarts.qld.gov.au/linesofdescent/works/zhang.html

With thanks to Senior Librarian Cathy Pemble-Smith and staff at QAGOMA’s research library.